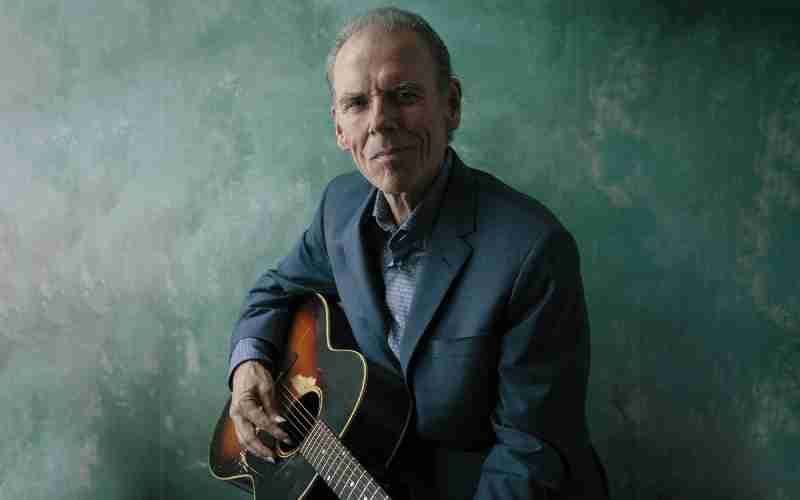

John Hiatt is not a household name, but he should be.

Pity the household that is not well-stocked with John Hiatt. But in reality, your household may be well-stocked with John Hiatt without you even knowing it.

Hiatt will perform with lap steel guitarist Jerry Douglas at the Clyde Theatre on Nov. 11.

Top Songwriter

Hiatt is one of the most consistently great and consistently praised singer-songwriters in the history of singing and songwriting.

His songs have been recorded and performed by Bob Dylan, Iggy Pop, Joe Cocker, Mandy Moore, and Paula Abdul. He has written hits for B.B. King, Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, Roseanne Cash, Eric Clapton, and Bonnie Raitt.

He earned a Lifetime Achievement in Songwriting designation from the Americana Music Association and a BMI Troubadour award. He’s in the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He has been the focus of three compilation albums on which various artists pay tribute to a single person.

Yet, he has only had one Billboard hit under his own name and in his own voice: “Slow Turning” in 1988.

Hoosier Roots

It all started in north-central Indiana in an idling car.

A young Indianapolis-born Hiatt was waiting for his mother to pick up a prescription at a Monticello drugstore and Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” came on the radio.

“I just remember that it had such a profound effect on me,” Hiatt said in a phone interview with Whatzup. “I thought maybe she wouldn’t recognize me when she got back.”

Hiatt was the sixth of seven children and life was hard. Hiatt’s older brother committed suicide and his father died after a long illness in a three-year span before he’d turned 12.

At 11, Hiatt got his hands on one of the cheapest guitars available and that was when he decided that making music was the only thing he really wanted to do.

“All the (expletive) hit the fan at 11,” he said. “I discovered the tragedy of loss and I discovered music and I discovered alcohol and drugs.

“Music really saved my life,” Hiatt said. “And, really, alcohol and drugs did, too, until it turned on me.”

After he turned 18, Hiatt moved to Nashville and was hired by Tree-Music Publishing Company as a songwriter.

Hiatt lived in an $11 a week boarding house with six other songwriters. Décor ran to bare bulbs hanging from the ceiling.

Hiatt described it as a wonderful time.

“I was 18,” he said. “I’d arrived on Music Row. I was being paid $25 a week to write songs. I thought I was a professional. From my vantage point, I thought I’d arrived.

“I was in a boat with a bunch of other songwriters of the day,” Hiatt said. “I loved it. I thought it was great. I mean, it was a beautiful way to learn to do what I do.”

Hiatt recorded two albums for Epic Records before being dropped because of low sales. He recorded two albums for MCA Records before being dropped for the same reason. He recorded three albums for Geffen Records. None of them charted and he was dropped.

His albums were critically acclaimed, but they just weren’t catching on with the public.

Hiatt admits that this was discouraging, but he also understood that it was just part of the process.

“It was pretty clear to me that this is just what I do,” he said. “As far as the fortunes that may or may not come from it, I was way less concerned with that and more concerned with becoming a better songwriter and singer and performer and a guitar player.”

Turning His Life Around

Eventually, Hiatt’s booze and drug habits caught up with him.

He remembers the date he decided to turn his life around.

“August Third, 1984,” he said. “I’d made a record that I don’t even remember making. That’s how bad it had gotten. I was estranged from my wife at the time. I had a three-month-old daughter, and I was driving around the southern United States just kind of lost.

“And all of a sudden, I couldn’t get drunk anymore and I couldn’t get high anymore, yet I couldn’t stop,” Hiatt said. “It was sort of like a living hell. So it was at that point that I made a phone call to a treatment center and said, ‘I am coming in. I am coming in for a landing.’ That was the beginning of my recovery. Thank goodness.”

Several months afterward, Hiatt’s wife committed suicide and he became a single parent to his daughter, Lilly.

In 1987, Hiatt finally found the combination of critical and commercial access that he so richly deserved. His album, Bring the Family, recorded with such backing musicians as might be enshrined on a musical Mount Rushmore (Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, and Jim Keltner), fired on all cylinders.

“I knew some magic was happening,” Hiatt said of the recording of Bring the Family. “We had a collection of musicians. It was kind of like a dream team. We kind of looked at each other, beaming. We didn’t want to pinch ourselves for fear it would just go poof.”

Bring the Family launched a string of comprehensively successful albums that ensured that Hiatt would be performing at the Clyde in 2021, and/or other things that storied artists with dependable fanbases do in their sixties.

Coming Full Circle

The same year that Bring the Family was released, Dylan covered Hiatt’s song “The Usual” for the Hearts of Fire soundtrack.

Considering the young Hiatt’s automotive musical conversion experience, having Dylan record one of his songs must have one of those full circle moments that most people talk about, but few know intimately.

“I was in disbelief,” he said. “The question was, ‘Why would he be doing one of my songs?’ But it was a thrill.”

Hiatt has a good feeling anytime somebody cuts one of his songs.

“It’s such a nice feeling,” he said. “It’s like someone saying something nice about one of your kids.”

Hiatt said the biggest change in his songwriting method over the last forty years is that he “doesn’t worry about it.”

Tom Petty dispelled a lot of the mystique of the creative process when he referred to successful songwriting as “getting one in the boat,” a fishing term.

Hiatt has always loved that analogy.

One thing he is still disciplined about is guitar practice.

“I pick it up every day,” Hiatt said. “It’s usually an acoustic and I play it for at least an hour.”

Hiatt and Douglas

The team-up between lap steel guitarist Jerry Douglas and Hiatt would not seem obvious on the surface. Hiatt is a blues-rocker and Douglas is a bluegrass musician.

But the collaboration produced some revelatory music. The two men brought things out in each other that had never been heard before.

Douglas will return to the Clyde in Nov. 28 as part of My Bluegrass Heart tour, an all-star bluegrass jam captained by Béla Fleck.

“He’s been bemoaning the fact that Béla’s songs are a lot more complicated than mine,” Hiatt said. “We were doing a soundcheck and he said, ‘How the hell am I going to remember all these Béla tunes when we go out?’”

Hiatt’s daughter Lilly is also professional musician.

Asked if he discouraged her from going that route, Hiatt said, “In every way possible.”

“I said, ‘What are you crazy? You’re out of your mind.’ She’s got the same problem I do. She loves the whole creative process. Just like me, it’s a three-legged stool. She loves writing the songs, she loves recording them, and she loves going out and singing them for people. That whole communion that takes place when you sing songs for folks, and they become involved in the making of the music.

“I wouldn’t want to take away any one of those aspects of what we do,” Hiatt said. “And my daughter’s the same way.”

Hiatt used to perform 150 shows a year, then he cut it back to 75, and then he cut it further back to 50 or 60.

He quotes B.B. King as having said that he doesn’t get paid for the two hours he plays. He gets paid for the other 22.

Which is to say, a musician gets paid for the wear of the road on bodies, minds, and families.

“You get in that cycle,” Hiatt said, “and you catch yourself 20 years down the road and you realize that you’re a professional musician but maybe a bit of an amateur person.

“That’s a phenomenon that I see quite often among my colleagues, and I had suffered from it myself. It took me a long time to grow up.”

Finally grown up at 69 and with the sort of established career that means he doesn’t have to tour incessantly anymore, Hiatt said he isn’t looking to retire anytime soon.

“I feel good,” he said. “And I still love playing and singing and that magic that can happen on a given night in a venue with a group of people.”

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event