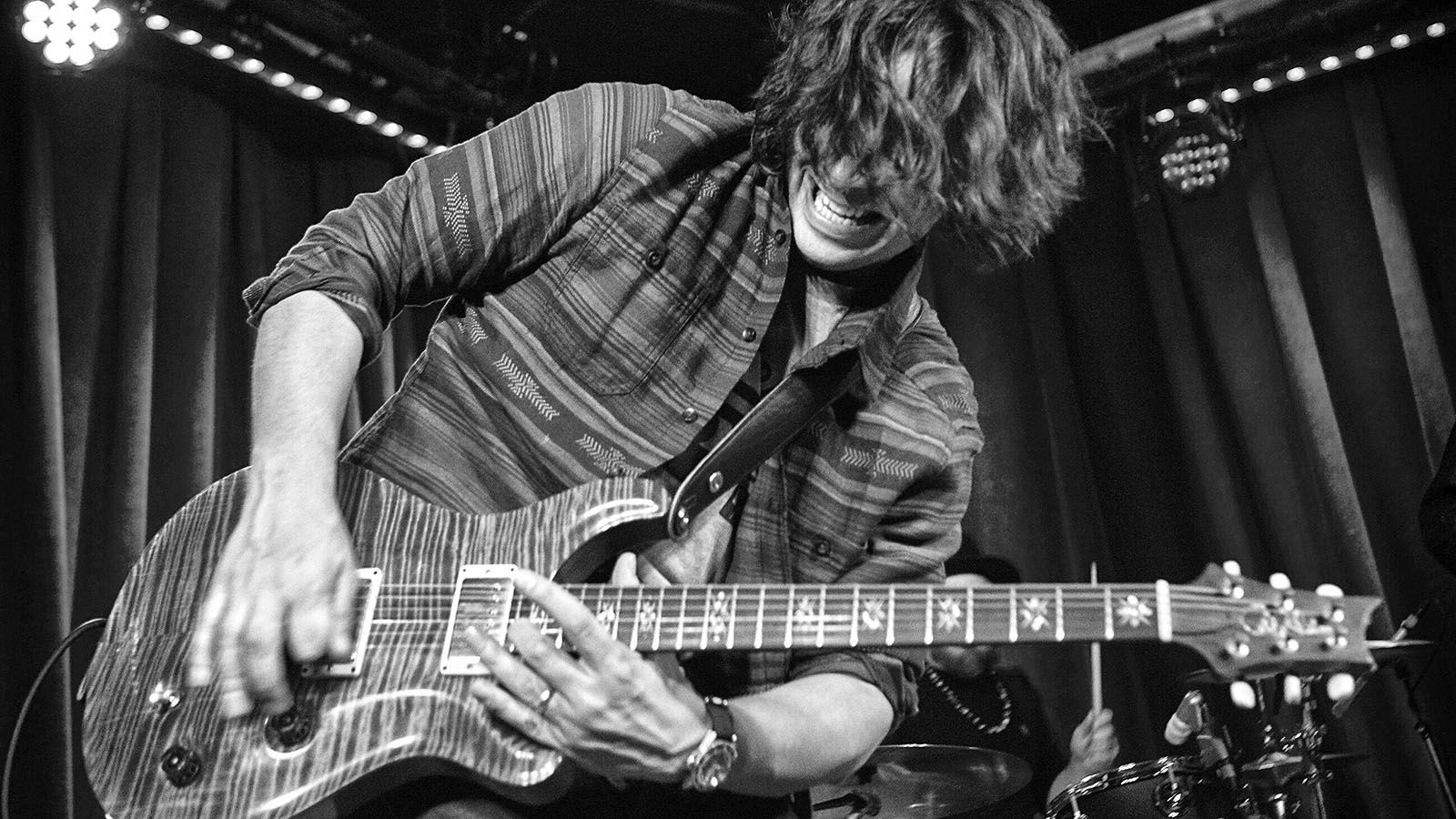

Davy Knowles is not technically from Britain, but he did grow up surrounded by it. A native son of the Isle of Man, the much-acclaimed blues rocker was still in his teens when he started his first band Back Door Slam, whose 2007 debut album Roll Away reached No. 7 on the Billboard blues chart.

Over the next two years, the group played hundreds of shows, including Coachella, SXSW, Bonnaroo, and Lollapalooza, before its members moved on to pursue other projects.

For Knowles, that meant going solo, sharing stages with the likes of Joe Bonamassa, Jeff Beck, and The Who, and becoming the first musician to play live directly to the International Space Station from Mission Control in Houston.

His latest tour kicks off Friday, Sept. 30, in Cleveland, then makes its way to Baker Street Centre the following night.

Knowles spent much of 2018 and 2019 on the road performing the music of Rory Gallagher with the Irish blues icon’s bandmates Gerry McAvoy and Ted McKenna.

Last October, he released his fourth album, What Happens Next, accompanied by accolades from musicians like Joe Satriani, who calls Knowles his favorite modern bluesman, and Peter Frampton, who’ said he’s the best gunslinger guitarist of the 21st century.

We recently checked in with Knowles to talk about Celtic rock, retro soul, and Britain’s fascination with American blues.

Q: You recorded What Happens Next with Eric Corne, who’s also produced a dozen albums by Walter Trout and a half-dozen more by John Mayall. Did you have any preconceived notions, before you went into the studio, that maybe changed while you were in there?

A: Well, I’m not sure that they changed. I’m a big fan of Eric’s work and had been listening to a Walter Trout record he’d done that I really loved. Walter is a much more traditional blues artist than I am, but even though it was a very honest representation of him, it also had this kind of modern edge to it, without sounding contrived. And I was looking for that for this project. So, I mean, the preconceived notion was thinking that Eric would be able to bring something a little more contemporary to it, and he did entirely.

Q: The song “Hell to Pay” has kind of a retro-soul, Daptone Records vibe to it. Is that something you were going for?

A: Oh, yeah. I’ve been a huge fan of Sharon Jones especially, and also Fantastic Negrito, folks that really have that soul element. So I just wanted to try and write in that style. And I was thinking, you know, “What would Sly Stone do with the vocal phrasing?” I’ve always loved his tune “If You Want Me to Stay,” and that was in the back of my head. So it was kind of an experiment, I’d never written like that, but I’ve always loved listening to it. God knows I am none of those people, but I was still really happy with it.

Q: Tell me about the Band of Friends Tour with Gerry McAvoy and Ted McKenna. I’m guessing there’s a big difference between listening to Rory Gallagher’s music and actually playing it onstage alongside his old bandmates.

A: Oh, God, yeah. Working with Gerry and Ted, who we lost, and then Brendan (O’Neill), who’s also kind of Rory alumni, what an honor. And yes, it truly was an education. Just the onstage work ethic and the kind of energy that Gerry was putting out, and also expecting from the rest of us. It was this idea of pushing each other, you know, “come on, come on, come on!,” and not always in a gentle way. I think it’s an old-school thing, and it really works. It’s fabulous.

Q: I once interviewed Rory Gallagher and he talked about how much he was influenced by Big Bill Broonzy, who at that point I’d never even heard of. Why do you think it is that people from the UK seem to know more about American blues than we do over here?

A: Well, I think if you move to a foreign town, like I live in Chicago now, right?, you notice that people here don’t go to the Millennium (Park) or other places like that. Because you’re living here, so you don’t bother. It’s always there, and you can go another time, no worries. Whereas if you’re just visiting, you make a huge effort. It’s like, “We’re going to do this, we’re going to do that.” And I think that, musically, it’s kind of similar. People like me view American folk music as a very exotic and important thing that seems so distant.

I mean, I can recognize folk songs in Appalachia that started out in my neck of the woods, for sure. But I have got no point of reference for a Black man in the South in a god-awful prison. I have absolutely no reference for that. And so when you have something that you can’t identify with, sometimes that pushes you to learn more about it, to study it, and, I don’t know, “understand” is the wrong word, but certainly to appreciate it, for better or worse.

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event