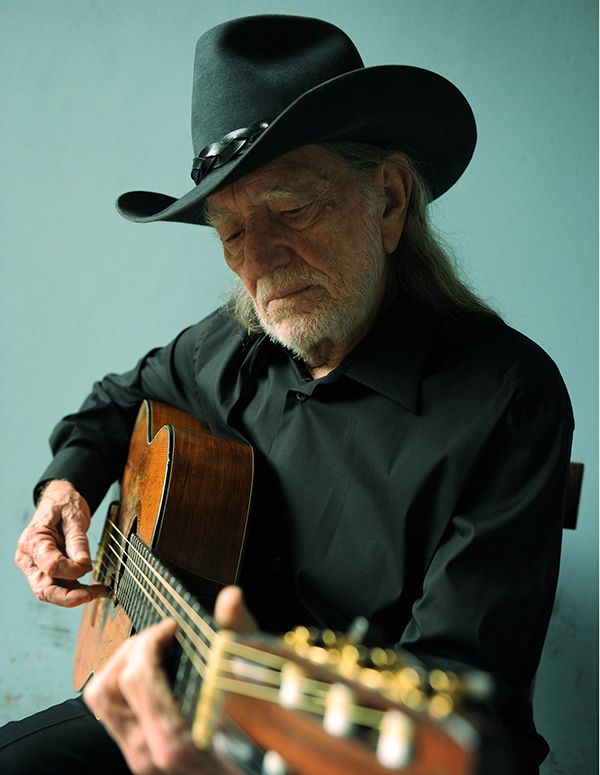

The title of Willie Nelson’s newest album – his 12th in 10 years – says a lot even if it doesn’t say it all. Last Man Standing is a musical rumination on aging, loss and death. It’s also upbeat and funny and down to earth, all the qualities that have helped make Nelson, who will take the Foellinger Theater stage Wednesday, June 27 at 8 p.m., such a beloved artist and public figure since his songs first hit the airwaves nearly half a century ago.

Nelson was born in Abbott, Texas during the Great Depression. Raised by his grandparents, he began writing songs at the tender age of seven and joined a band three years later. His family spent the summers picking cotton. Nelson hated the work, so earned money by singing in dance halls instead. Clearly, he was made to make music, but as a young man he took a few stabs at a more conventional lifestyle, joining the Air Force in 1950, only to be discharged for back issues, and attending Baylor University where he lasted two years studying agriculture before dropping out to sing, write songs and play guitar full time.

He still had to make a living, and Nelson, now a married man, supported himself and his family working as a bouncer, saddle maker, tree trimmer and parts man in an auto supply store. Later, he secured a job as a disc jockey with a Pleasanton, Texas radio station, and it was there that he recorded his first two songs: “The Storm Has Just Begun” and “When I’ve Sung My Last Hillbilly Song.”

It was a beginning, but Nelson still had a long way to go. The next decade reads like a someone’s last hillbilly song. He moved to San Diego but was unhappy there. Then he tried to hitchhike to Portland, Oregon where his mother lived, but no one picked him up and he ended up sleeping in a ditch. Eventually, he hopped a freight train that got him halfway but dumped him, broke, in a railyard. Then he borrowed money from a trucker to finish his journey. Now 23, he was hired again as a disc jockey, this time in Vancouver, Washington, where he made regular appearances on local TV. Then it was onto Colorado and Missouri and finally back to Texas where he sold Bibles, vacuums and Encyclopedia Americana door-to-door.

He paid his dues, in other words. He lived the life of an everyman, and he worked hard to support himself, his family and his dream. He finally began selling songs to band leaders and nationally known singers in the late 50s, and he moonlighted in nightclubs in and around Pasadena, raising a son and giving guitar lessons.

Nelson always knew he has something special to offer the world of music, and, like so many before and after him, he made the move to Nashville. It took a few more years of scrimping and striving, but in 1961, having met many of the city’s country luminaries in and around the Grand Ole Opry, he had the honor of seeing a number of his songs picked up by the likes of Roy Orbison, Billy Walker and Patsy Cline. Cline, of course, recorded Nelson’s “Crazy,” which went on to become the biggest jukebox hit of all time – probably because it’s all about pining and loneliness and hopeless love, perfect for nights when one only has a stack of quarters for company.

Nelson has never stayed in one place for very long. Following the release of his first studio album, …And Then I Wrote, he moved to California, writing for Pamper Records’ West Coast office. Then he moved back to Tennessee, where he bought a ranch. He kept writing music, met Waylon Jennings, formed a band, dissolved the band, invested in a number of tours that failed to make money, got divorced, got remarried, divorced again, saw his ranch burn down and, disillusioned with the music business, retired from songwriting altogether. It was 1972 and he was 39 years old.

Time, he thought, to move back to Texas. This go-round, he picked Austin as his home base, and it was in that free-thinking, free-wheeling town that Nelson rediscovered his love of music, thanks in large part to the city’s burgeoning hippie scene. Nelson began playing out again, mixing honky-tonk with jazz and folk and pioneering a style that would soon be called “outlaw country.”

In 1973, he put out Shotgun Willie, one of the most seminal albums of his career. It was a success with critics but sold modestly. Still, Nelson was pleased because he was finally making the kind of music he wanted to make. He followed that up with Phases and Stages, a sort of “he said, she said” look at divorce, and then in 1975 came worldwide fame, thanks to the concept album, Red-Headed Stranger.

Nelson was a stranger no more. He was a household name. His friendship with fellow outlaw country star Jennings led to a number of popular duets and the Platinum album Waylon and Willie, and in the 70s it seemed that everything Nelson wrote and recorded charted and gained him more fans. It was the decade of “Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys,” and “Good Hearted Woman” and “If You’ve Got the Money, I’ve Got the Time.”

It’s easy to say that the 70s were Nelson’s heyday, but he never stopped recording music, making new friends and growing as an artist and advocate. In his career, he has put out more than 60 studio albums, and that doesn’t count the live recordings and collaborations. He’s also appeared in countless TV shows and movies (everything from Honeysuckle Rose to Half Baked and A Colbert Christmas: The Greatest Gift of All) and written nine books, including The Tao of Willie: A Guide to Happiness in Your Heart and It’s a Long Story: My Life.

It might indeed be a long story, but it’s one that only gets better with the telling.

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event