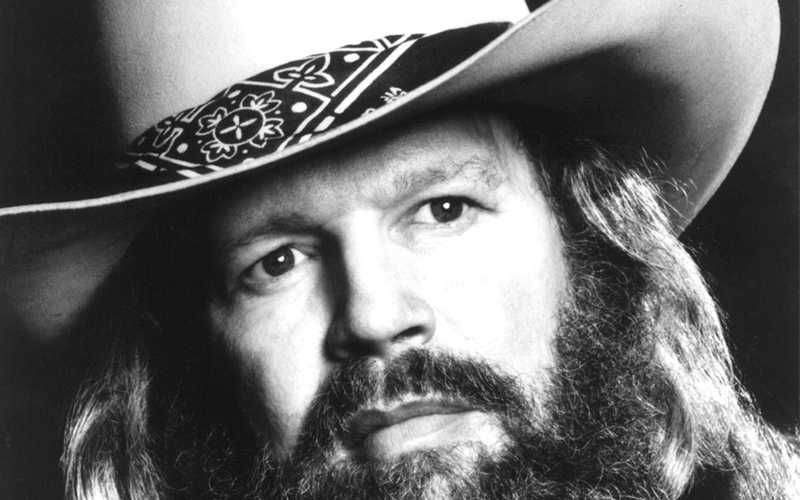

Sifting through David Allan Coe’s biography, it’s not easy to sort out what’s true and what isn’t.

Coe has been such a polarizing figure throughout his decades-long career, he’s inspired his detractors to tell stories about him that are almost certainly not true.

He’s also been known to tell stories about himself that are almost certainly not true.

The truth probably lies somewhere in the overlap, and even if it’s less spectacular than some of the myths, the truth is undoubtedly sensational.

Earning a bad-boy image

One fact of Coe’s biography that’s unquestionably true is that he is one of the original practitioners of outlaw country music. One of his most enduring origin stories has him parking a gaudily decorated hearse in front of Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium and busking to get attention in the late ’60s. This myth is likely true — there are pictures — and Coe’s debut album, Penitentiary Blues, was released in 1969, thanks to all that attention seeking.

Through the early ’70s, Coe cultivated a bad-boy image, but he wasn’t a make-believe outlaw. He was a real outlaw who had already been to prison more than once — although he probably hadn’t been on death row as he claimed — and songs like “Longhaired Redneck” exemplified his bad attitude.

His biggest hit, though, came in 1977 when Johnny Paycheck covered “Take This Job and Shove It” and took Coe’s song to the top of the charts.

That Coe’s biggest hit came only when someone else sang one of his songs is par for the course. Although he was making a name for himself among outlaw country fans, he was much less successful at widening his appeal.

Consider his third album, 1974’s The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy. The record was praised by critics but produced no hits. When Glen Campbell released an almost identically titled album the very next year, its title single, “Rhinestone Cowboy,” was a cross-over smash that reached number one on the pop charts.

Staying on the fringes

While his fellow outlaws — Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings most notably — were leaning into mainstream success, Coe predictably remained belligerent and went in exactly the opposite direction. In 1978, he recorded an album of songs that his record label would never touch and sold it via mail order through an advertisement in the back of the outlaw biker magazine Easyriders. Another self-released album, creatively titled Underground Album, followed in 1982.

These two albums would define the darker side of Coe’s career. Intended as bawdy humor, they contained songs that were so racist and misogynistic that The Guardian has deemed them among the most offensive albums of all time. Whether Coe is genuinely racist or not — he insists that he isn’t — the albums guaranteed that he would remain on the fringes of the music industry for years to come.

In the early ’80s, Coe had a momentary mainstream resurrection, as 1983’s “The Ride” delivered a safe bit of nostalgia for Hank Williams and 1984’s “Mona Lisa Lost Her Smile” tread the unoffensive territory of love ballads. Both songs hit the top 10 on the country charts, but they were likely the last time Coe would get within sight of the top of the charts.

Remaining an outlaw

By the turn of the century, Coe’s penchant for saying whatever he thought — and not caring whether or not he offended — had become a virtue in certain circles, and a new generation of musicians were open about their admiration for the original outlaw.

Among them were Kid Rock, who has both toured and written with Coe, and Hank Williams III, who recorded a single, “The Outlaw Ways,” with Coe in 2013.

These days, Coe is still an outlaw, although his transgressions are perhaps a bit more mundane than they used to be. In 2015, he pleaded guilty to tax evasion, but his conviction resulted in probation rather than a prison sentence.

At age 79, Coe’s health is starting to become a source of myth, too. He claims that a hospitalization that forced him to cancel a performance last year was for an inner ear infection, and says that reports that claimed he’d had a stroke are lies.

One thing is for sure: David Allan Coe will always keep you guessing. His performances are legendary for their grab-bag nature. Sometimes he’ll change the lyrics to songs, and sometimes he’ll stop in the middle to tell a story. One minute he’ll belt out a profane, offensive tirade, and the next he’ll serve up a poignant ballad. He does what he wants on stage, nothing more and nothing less. If that’s not an outlaw, nothing is.

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event