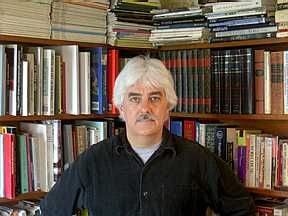

Consider this description of a

12-year-old work as a not so simple, but

revealing portrait of local philosopher/artist

Jeff Strayer: The piece, enclosed in a

30-by-50-inch frame and behind glass, defies

photography. It is hung upon a narrow upstairs

hallway wall in a weathered early 20th-century

wooden home in the city’s near west end. The work

once hung briefly in the Fort Wayne Museum of Art

and contains mounted 35-mm expended film

canisters, some black and white photographs and

other documentation which amount to archival

evidence. It was part of a mid-1990s exhibition

“For the Love of Art,” initiated by former museum

Director Emily Kass and designed as a way to

involve local artists and raise money.

“Emily had this idea of giving out first chairs,

then, later, small hobby horses to artists who in

turn were to paint, decorate or otherwise

manipulate and submit them for a showing,”

recounted Strayer who has lectured Philosophy,

Ethics and Aesthetics at IPFW since 2002. “The

Dadaists took their name from the French word

“dada,” which translates as hobby horse. So

rather than just decorating the horse I devised

another, two-part approach.”

Strayer first photographed the interior of the

City County Building lobby from eight positions

then mailed the undeveloped roll of film to an

address picked randomly from the local phone

book. Simultaneously he packaged the hobby horse

in a plain box and sent it, also without

instruction, to the mayor’s office.

“You have to remember,” Strayer continued, “this

was in the ‘Unabomber’ days. But Mayor Paul

Helmke just opened the package and placed the

miniature horse on his credenza without much

attention.”

If you want a definition of conceptual art,

that’s it. Taken a step further it was a case of

a Trojan horse of a different color. For Strayer

the actions were a composition using elements of

chance, historical reference and humor. A

performance that resonates with the dictum that

artistic knowledge trumps the art object

itself.

The 55-year-old Strayer began his pursuit of the

subject-object relationship while growing up in

Warsaw. The oldest of three children (his father

was an insurance agent and real estate investor,

his mother a homemaker), his early readings in

philosophy (especially Bertrand Russell) and art

led him to earn a BFA at the University of Miami

(Florida) and. later, his MFA from Chicagos Art

Institute.

To support himself Strayer embarked on a

teaching career, first at Saint Francis and then

onto IPFW, concentrating on Philosophy. For a

measure of the depth of his studies visit his

online syllabus where you will discover an

intimidating outline of readings in essentialism,

epistemology, metaphysics, philosophy of logic

and aesthetics.

Meanwhile back at the ranch, the home he has

shared for 10 years with Angela Boerger, the

well-regarded marketing and political consultant

and their cat, Zeus, “the real ruler of the

house,” Strayer cultivates the time and space he

needs.

The artist moves easily between three separate

spaces in worn leather shoes and rumpled pants.

The largest space, converted from the original

first-floor parlor/dining room is his working

studio, replete with a drafting table and a

large, specially lit table surface and assorted

tools. On the second floor a small room is

equipped with a computer and serves as his

writing room. Across the hall is another small,

book-lined enclave where I suspect most of his

work goes on. Two of its walls are filled floor

to 10-foot ceilings with books on art criticism;

the third is laden with works on philosophy, and

the fourth with a collection of scientific

treatises ranging from evolution to quantum

theory.

In the center of the room sits a small desk upon

which rests two thick unabridged dictionaries

opened as one would find them in a classroom or

public library. Cradled on top of the science

bookcases rests another pair of large

dictionaries.

It is here where Strayer smokes his tobacco pipe

and where he conjures up the content of his book

manuscript due to the publisher in September. Its

title: Subjects and Objects: Essentialism, Art

and Abstraction (an earlier abbreviated

version is contained in the above mentioned

citation on Strayer’s IPFW Philosophy of Art 575:

Advanced Problems in Aesthetics).

Okay, stop and take a breath. I know this is

thick stuff. but it is relevant to our subject

here. Maybe Keats’ lines closing his Ode On a

Grecian Urn will help us with some

disambiguation:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,-that is all

“Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

To a large extent philosophers don’t always

make the best writers, Hegel and Kant for

example,” advises Strayer. But that is not the

case with his own work, as he has had several

papers published. In addition, as a member of

both the American Philosophical Association and

the American Society for Aesthetics, he has

presented papers at those association conventions

and several other academic settings, including

upcoming appointments in Milwaukee and

Toronto.

As to his art, Strayer continues to produce,

although less frequently with writing deadlines

looming. Subtle-colored, abstract and text-driven

pieces are the core of his collection. Major

painters like Rothko, Mondrian, Reinhart and

Newman have impacted his earlier paintings. They

have been shown as part of numerous local and

regional galleries and museum exhibitions.

In his most current work can be found traces of

the likes of his favorite minimalists – Joseph

Kosuth, Donald Judd, Carl Andre and Sol

LeWitt.

“Some art is so technical and intellectual that

it is like philosophy, theoretical physics or

advanced mathematics,” Strayer said in response

to a query about the conventional assumption that

one must be an intellectual to appreciate art.

“Artists who are producing work of this kind, me

included, are concerned with establishing

boundaries that certain kinds of creative

investigation allow. And just as theoretical

physics cannot be understood without a great deal

of education, the same is true of certain

artworks.”

Strayer’s reoccurring theme exploring the

object-subject is very evident in a series of

five small saddle-stitched paper bound books

variously titled Decisions, Untitled

No. 5, Still Life with Fruit, Wine,

Audiotape and Projections, Intentions

and Portrait of An Unknown Lady.

Originally published in New York in 1982, the

limited-edition collection is part of several

prestigious American museums, including the

Metropolitan and Modern in New York, the Art

Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Museum

of Art.

These personal and sometimes confessional

anecdotal slices of his life incorporate concrete

poetry, 35-mm slides, typographic expressions and

film negatives which give the viewer X-ray images

of what the artist was up to at the time. Like

ribbon-tied bundles of letters retrieved from the

attic or imbedded codes launched into space via

Voyager, these chapbooks have become

archeological clues to their time and place.

Strayer is not a one-or even two-dimensional

man. His outside activities include hiking

(10-15-mile treks), food and cooking (he’s never

met a cuisine he didn’t like, including black

bear in a Norwegian restaurant), traveling (he

gets to Europe as often as he can and would like

to settle there), the cinema (he loves foreign

films; Fellini is a favorite) and music,

especially classical (his favorite 20th-century

composers are Elliot Carter and Ralph Vaughan

Williams).

Taken together Strayer’s accomplishments and

interests make a classic recipe for a supreme

cosmopolitan and citizen of the world.

He’s been known to sit as a panelist in the

“Crit!” series at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art,.

Catch the next one and experience him first

hand.

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event