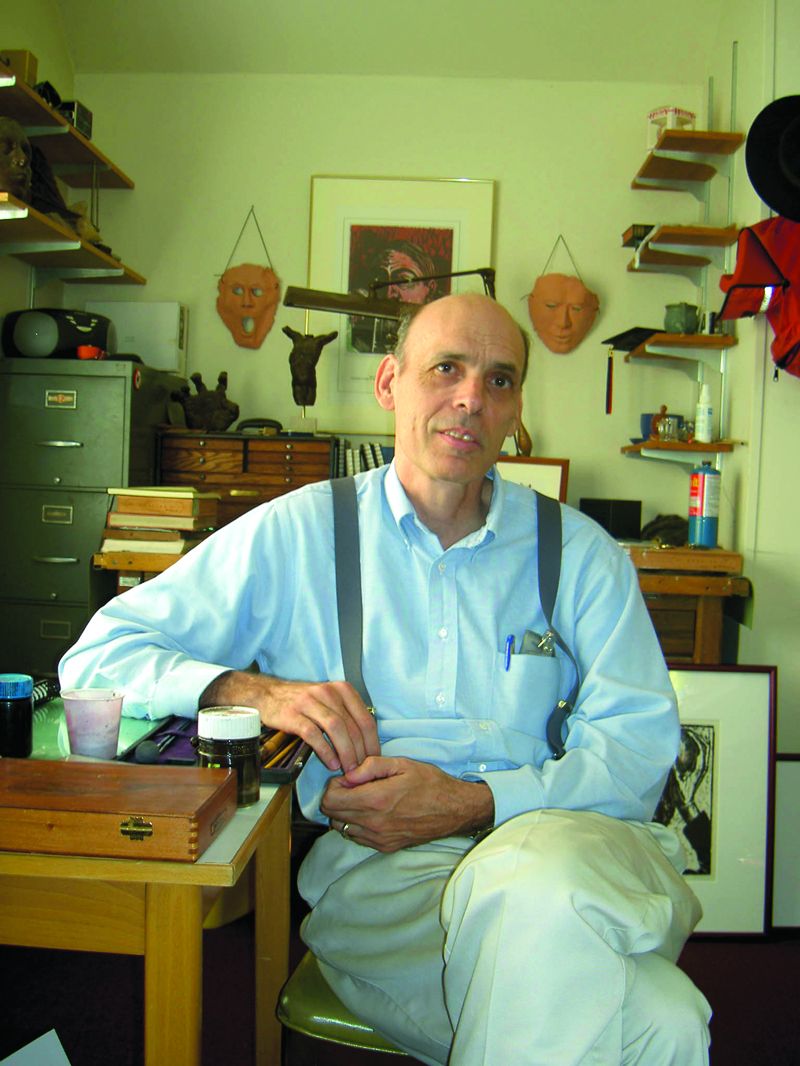

Pretensions are out the window when you meet Art Cislo in his studio at his quaint South Side home. Clad in suspender-hung khakis and his traditional blue cotton shirt and sandals, the 58-year-old, balding printmaker cuts a striking figure of humility and grace. Against a backdrop of dozens of wooden blocks and countless paper proofs Cislo exudes a sort of old country image that matches in some ways the directness and simplicity of the ancient art and craft of woodcutting and monoprinting. A desk lamp and a small radio provide the only links to modernity in the small upstairs quarters of the 65-year-old house where he works. The slight aroma of cherry wood shavings and the tinge of printer’s ink season the atmosphere and trigger memories of bygone, more simple, less turbulent times.

Cislo (it’s Polish, could be rooted in “tree” and is not an uncommon name in Detroit where he grew up) is one of three award winners from Artlink’s 2002 Regional exhibition, and a generous collection of his recent work is currently being featured at the gallery through November 5.

After graduating from Wayne State University where he majored in drawing and sculpture, Cislo found work here at International Harvester (now Navistar International) in the industrial design division where he was initially a clay modeler before retiring as Service Publications Coordinator after 31 years.

A unique career you might think at first glance, until you learn that Cislo’s father also worked in the automotive industry as a designer for the venerable Ternstedt Company which produced those wonderful hood ornaments of days past. Remember those over-the-top rockets, flying ladies, tall ships, gazelles, greyhounds and swans? Eventually all that chrome and the brass moldings disappeared, as designers sought cleaner, sleeker styling, but it’s easy to connect the artist’s gifts for line, form and creativity with his dad’s vocation.

These days Cislo teaches drawing in the University of Saint Francis Art Department where he once earned a graduate degree in Business Administration. When not in the classroom Cislo busies himself in pursuit of his passion which he generously shares with other artists and printmakers. Since he doesn’t have a press at his studio, Cislo is happy for the added value of his job: access to the department presses

A familiar history perhaps, but one that can’t be overtold: woodblock printing originated in Egypt and China and didn’t hit the West until around the 12th century when, along with the oriental gift of paper-making, examples began to appear in Spain. The textile industry was first to make use of block printing, but it took the development of mass-produced paper in the early 14th century before the artistry of the woodcut surfaced.

Initially woodcuts emerged as a medium for mass consumption in connection with the production of religious icons, often as handbills sold to pilgrims visiting holy sites. Profits from these “bull’s eyes” and “evil eye” protectors were used to sustain the Crusades as well as to fund the early attempts by Gutenberg and others to develop the technology for moveable type.

For generations the form was employed primarily to illustrate religious and botanical texts, but by the late 15th century artists like the Italian Titian, the Germans Durer, Holbein and the Dutch master von Leyden began to explore the medium in new and exquisite ways. In their hands, so to speak, the art of the woodcut grew from Durer and others who employed artisans to proliferate their work to mass audiences, and the notion of facsimile was borne.

The artist would draw, scribe or pound their images on wood planks (walnut, pear wood and boxwood), then turn them over to skilled carvers, many already schooled in the arts of metalsmithing, who would render them over and over, not unlike a modern day Warhol and his “factory.” Somewhat later the woodcut as a means of artistic expression gave way to line engraving on metal or its opposite, copper intaglio, although it continued as the main medium for the expanding publishing industry largely because of its economy.

Some 500 years later, in the late 19th century, the art form again became of interest as a means of aesthetic expression. Gauguin produced works based on Japanese prints of the Edo period he saw in Paris, and the Norwegian Munch used the medium to great effect. About the same time the German Expressionist movement explored the form and helped to spur interest in it as a contemporary form. (There are tons of examples available through your favorite search engine, including the incredible Japanese work known as ukiyo-e.)

But it is to these German artists — Kirchner, Nolde, Heckel, Mueller and others known as the “Brucke Movement,” as well as Beckman, Kandinsky and Klee — that Cislo owes perhaps the most. The essence of their spare, primitive and highly personal works is evident in Cislo’s portfolio. The purity and exactness of the carved, gouged and chiseled surfaces and their resultant prints are amazing to behold in the woodcuts and are matched in the deftness of line in his monotypes.

Like his mentors, Cislo has remained selfish about his craft, and he has reserved the right to carve, expose, lift and reveal for himself with tools only slightly changed from the time they were first invented. A hand-full of u- and v-gouges, bull noses and Exacto knives — Dremels are unwelcome — give him the necessary utensils to create the negative space he’s after.

Nearly all the Post-Abstractionist painters — Dine, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Kleinholz, Stella among them — at one time or another explored the possibilities of printmaking, including woodblock, but Cislo holds them to be secularists in a sense, guilty of exploiting the medium rather than embracing it. Not that he doesn’t appreciate their work; it just rubs against the grain of tradition.

Dominant in the subject matter of what is on view at Artlink is a series depicting the last story in the New Testament of John the Baptist, a subject previously visited by the iconoclast Pop artist, Jim Dine in his opus The Apocalypse, The Revelation of Saint John the Divine in 1982. It is no doubt more a matter of coincidence than imitation.

“Maybe because I’m a parishioner of St. John’s it became an obvious choice for a theme,” explained Cislo, “but also it’s a great story. The manipulation of people propelled by self-interest, the psychology of humanity, it’s just all there. Like in Shakespeare and in other great literature, G.B. Shaw’s Joan of Arc and so on, there are lessons there, and in the telling of the tale I found a vehicle that moved me.”

There are other pieces, sans religious themes, like the soft, delicate portrait of a young poet and a table scene, more erasure than carved relief, entitled Fish Today, where Cislo shows off his gifts for subtlety in expressing mood.

Perhaps I’m guilty of hyperbole here, but I can’t escape the notion that, having seen the show and spent time looking at dozens of other pieces in his studio, I have been in the company of a master. I know my assignment here was to look at the Artlink show, but there’s a richer vein that is deserving of more public exposure.

In the late 1980’s Cislo designed the poster for the local Civic Theater production of a play based on Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 which remains outstanding, as do some preliminary pieces on the same theme. A series of colored works done for a contest to illustrate one of James Joyce’s novels (Ulysses or The Dubliners, I can’t recall which) seem to me to be of the highest quality, along with his several studies of the female form.

No epigone here, Cislo is a prolific journeyman and genuine treasure.

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event