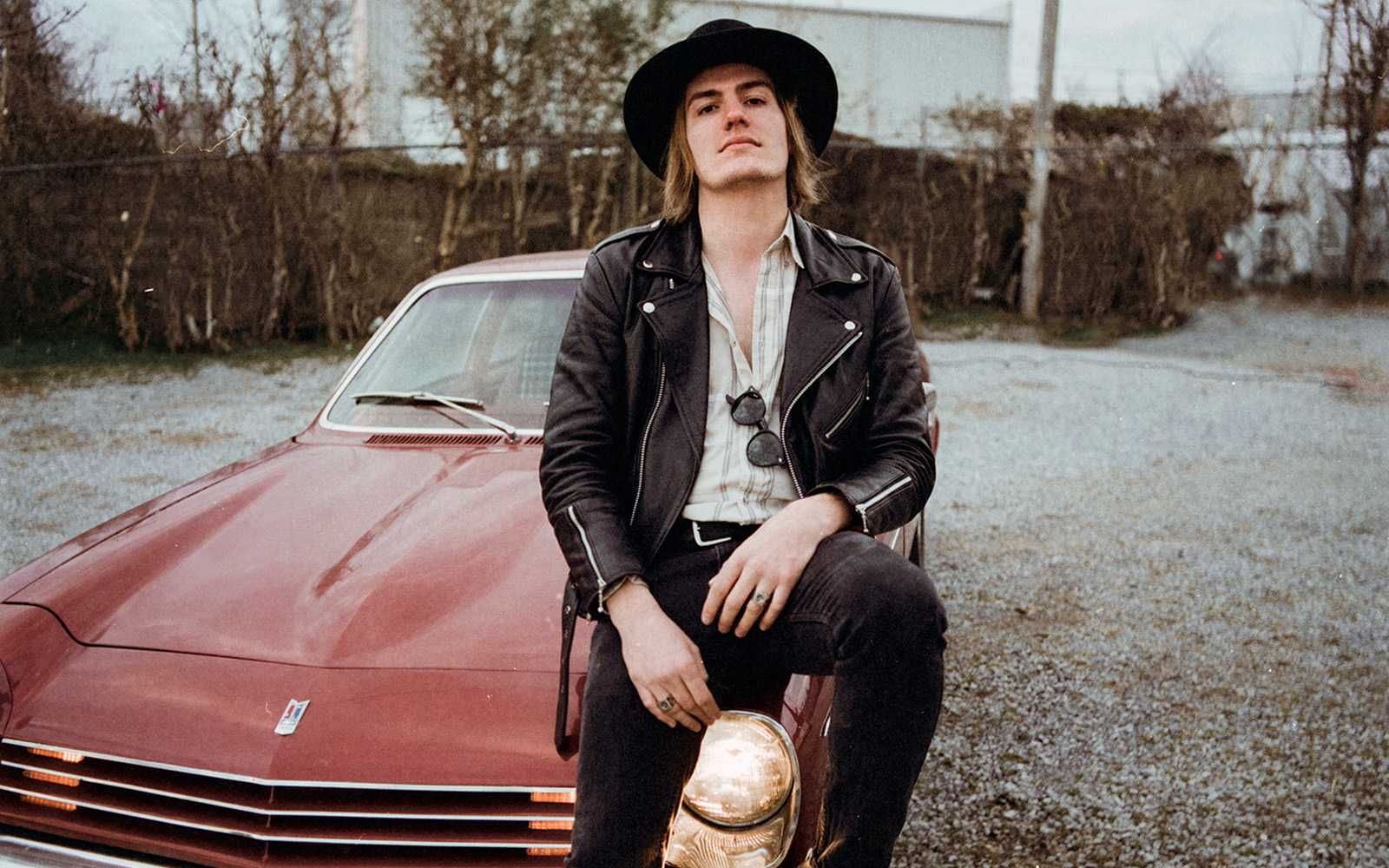

Dylan LeBlanc spent part of his childhood in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, with his musician father.

As a boy, he’d listened to the music other kids were listening to at the time: pop-punk bands like Blink 182 and Linkin Park.

But the music he was driven to create as a teenage singer-songwriter seemed to have no antecedent.

“I was writing songs that weren’t like what the other kids were listening to,” he said in a phone interview with Whatzup. “It was in my subconscious so much that I couldn’t get it out. I couldn’t write any other way. I wanted to.

“But I was glad I had that in me. I was always drawn to the more melancholy music. I don’t know why that was, really.”

Ben Tanner, a cohort of his dad’s and a member of Alabama Shakes, began slipping him mix CDs and MP3s of artists that he thought LeBlanc would like, such as Wilco, George Harrison, Ryan Adams, Bruce Springsteen, Jeff Buckley, and My Morning Jacket. It was in this way that LeBlanc found his musical tribe.

Appreciating songwriters

What immediately strikes a person about Le–Blanc’s songs is how exquisitely well-written they are. They grab a listener straight away and don’t let go for four minutes.

One of the benefits of growing up in Muscle Shoals for an aspiring musician is that he learns to appreciate songcraft.

“There were so many great songwriters around,” LeBlanc said. “You would never want to play a song for anyone that wasn’t your best work because everyone knew what a great song was.”

LeBlanc entertained the typical dreams about rock stardom as a boy, but one of his father’s many knowledgeable colleagues told him something that shifted his view.

“He said, ‘All those people—the reason why they are rock stars and the reason why they made it so far is that they had songs,’” LeBlanc recalled. “’They were songwriters before they were any of that.’”

LeBlanc came to understand that songs were the only currency in the music business: Success was conditional upon the quality of songs.

Slow and steady success

LeBlanc is an enormously respected artist these days, but the journey to this place was slow and arduous. There were many moments when almost no one in his life thought he was doing the right thing.

“People were like, ‘You need to find a real job. It’s time to give up the pipe dream,’” LeBlanc said. “When your girlfriend is working full-time and you’re trying to make it, it’s embarrassing. There was a lot of humiliation there where I was like, ‘Maybe I am just not good enough for this.’”

In LeBlanc’s family, there has never been anyone with deep pockets. His first album, Paupers Field, was put together with good fortune and favors.

Monty Hitchock, LeBlanc’s manager at the time, convinced Emmylou Harris to come in and duet with him on “If the Creek Don’t Rise.”

“She told me to tell her if there was anything I didn’t like,” LeBlanc recalled. “And I was thinking, ‘You’re Emmylou Harris. There’s no (expletive) way I am going to tell you that I don’t like something.’”

One last stand before giving up

LeBlanc’s extraordinary third album, Cautionary Tale, was recorded at a time when LeBlanc was on the verge of giving up on music…and maybe more.

Tanner and John Paul White had scored a splashy success (the first album by St. Paul and the Broken Bones) on their nascent record label (Single Lock Records) and this allowed them to record Cautionary Tale.

“They took a chance on me,” LeBlanc said. “I was very lucky that they were there because I don’t think I’d be here right now if it hadn’t been for those two people.”

As confident and persuasive as Cautionary Tale sounds, LeBlanc said it was conceived in “desperation.”

“I mean, there was so much desperation in that album,” he said. “So much asking the universe for so many things. That record needed to happen. I needed it so badly at that moment in my life.”

As great as Cautionary Tale clearly was to most sentient humans, it did not lead directly to fame and fortune. LeBlanc has yet to be discovered in the way that, say, Billie Eilish has been. He has never experienced sudden ubiquity.

“There was a long, long, long, long period of time when I wasn’t making any money on the shows or records,” he said. “It felt like nobody liked it. It was really hard to get people in the room for shows. I’ve had a very slow career.

“Sometimes you get down about it,” LeBlanc said. “People would say, “Oh, he’s Ryan Adams 2.0.’ And you’d think, ‘You know what? (Expletive) you!’ People say (expletive) like that and you’ve got to get out of your head about that and stay true to yourself, try to find your own thing and stick with it even when people aren’t there to support it.”

Fighting addiction

LeBlanc said it was only about four years ago when he began to feel that his career was making real headway.

“You grow one fan at a time and, before you know it, you have thousands of fans,” he said. “It is more gratifying the way I have done it. Because I know every person in the audience of my show, they want to be there.”

There were times, LeBlanc admits, when he was one of the biggest barriers to success.

He has struggled with alcohol addiction and was arrested in New Orleans in 2014 for being drunk and disorderly.

“I’ve had 70 days without a drink,” he said. “I had a very painful relapse recently. For me, I can’t do it well. I don’t drink well. When I am on the road, I have to remember that.”

LeBlanc knows two things now about himself “beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

“I didn’t create myself,” he said. “I don’t know what did. I know it doesn’t matter. And I don’t drink worth a (expletive).

He spat that last part out with self-directed venom in his voice.

“I just don’t drink like other people. I pay consequences when I drink,” LeBlanc said. “I am a different person when I drink. Anything that is gone in my life that I loved and I don’t have anymore, I can trace back to a disturbance inside myself that made me want to drink.”

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event