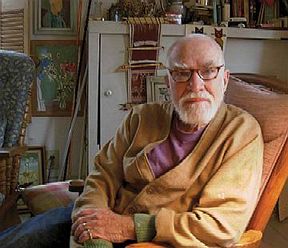

A pilgrim with perhaps tens of thousands of miles under his belt artist George McCullough doesn’t give you the feeling that he’s been in pursuit of the meaning of life or, for that matter, anything. The soft-spoken octogenarian’s role seems more that of a citizen of the world, surveying his shared domain, immersing himself in its wonders and incessantly documenting its features through his work.

Retired now after nearly a quarter-century of teaching at the original Fort Wayne Art Institute and later at Indiana-Purdue Fort

Wayne, McCullough and his wife Sue, the accomplished weaver and quilt-maker, continue to create in the 120-plus-year-old home in the city’s near north side which they purchased in the 1960s.

The original two-story wood-framed house, a small cottage across the street and a backyard studio – all filled to the brim with objects d’art, assorted looms, toys, stained glass pieces and kitsch knick-knacks – have acted the dual roles of a kind of playground for the couple and a sanctuary for local artists.

As much a fixture of the local art landscape himself, the still prolific McCullough heads up the current show, “Open Air Painters” at the Kelly Gallery which features Fort Wayne parks and landscapes and will continue its run for a month. The gallery, located in a former carriage house at 818 Fulton Street, is part of Kelly Advertising. Viewing hours vary and can be arranged by calling 260-426-1843.

Besides McCullough, the exhibition features the works of Bill Quance, Don Kruse, Don Osos and Tom and Matt Kelly. Taken together, the show could be viewed as a slap and slash cornucopia of light and color, frame and field, vision and expression in a kind of “battle of the palettes.”

Each of the artists show, even strut their stuff in these mostly spring and summer scenes (the Lakeside Park fountain, rose garden, views of the three rivers are reoccurring images), and as accomplished and professional as they are, this assortment runs the risk of being dulled by sheer conformity if not in style or imitation. That said, Osos and Kruse deftly stand apart, having dipped their brushes and pens in a color and style pool from a different school.

McCullough’s travels – and, indeed, there have been many – began in Long Beach, California where, despite a cultured working-class background, he was never really inclined toward an art career. It took the calamitous events of World War II (he was 18 when Pearl Harbor occurred) to spark an interest in the fine arts.

After spending two years at Los Angeles City College he joined the Army Air Force with the hopes of becoming a pilot. But following a disappointing dismissal from aviation school, the Army assigned him to a job as a flight traffic clerk with Army Transport Command, where he served during the years 1944-1945 in the Pacific Theatre, flying back and forth from California to Australia, New Guinea, the Philippines and Okinawa.

Often based out of San Francisco, McCullough began exploring the formal study of art (largely because of the number of women in the classes, he claims), and through his acquaintance with a teacher he settled on the University of Iowa, which was known for his painting department and famous faculty (Grant Wood, Philip Guston), to study.

After gaining his undergraduate and Masters degrees in Iowa City in 1949, McCullough was awarded a Fulbright scholarship and spent the next two years studying the classics at the Academia Belle Arti in Florence and the Academie de la Grande Caumiere in Paris.

Upon his return to the States and after a brief stint in Montana where he discovered Sue, he decided to settle in New York City, where he found work initially as an embroidery designer in the garment district. The money was enough to cover the $19-a-month rent for a Lower East Side tenement flat and materials to continue to paint on the side.

“The place was on East 10th Street,, a neighborhood filled with Ukrainians and Puerto Ricans. My telephone number was Canal-3678, and I remember lots of wonderful parties with bathtubs of iced beer,” McCullough recalls.

“I hung out sometimes at the Cedar Bar and the White Horse Tavern with the likes of painter Franz Kline and the writer, Norman Mailer. In fact, I once took over Mailer’s apartment to use as a studio after he was kicked out for hosting a wild party. It was difficult then, as it is today, to get a show, but I was part of several group shows in the church, St. Mark’s in the Bowery, which remains a vibrant venue for poetry, art and politics even now.”

Although he was exposed first-hand to Kline and the works of Hans Hoffmann, McCullough never quite bought into the then shocking abstract expressionism school of painting, and he remains a faithful figurative painter.

After leaving the Big Apple in 1960, McCullough found work at City Glass designing stained glass pieces and then ran into his former classmate and friend Russell Oettel who was directing the Fort Wayne Art Institute and offered him a teaching position. The rest is, as they say, history.

“There was a great sense of spirit at the Art School,” McCullough remembers. “There was a lot of serious work going on in the studios. Many students lived nearby the school, so there was a community of art. Of course, you didn’t have to take part in it, but I think the students grew from the interaction.

“Things are different these days. I don’t sense the same curiosity. Perhaps we’ve made it all too easy for this generation. Sometimes I want to stop a student and just ask them to show me what they are carrying around in those heavy knapsacks. Of course, I’d get arrested, so I’ve never done it, but I’m still curious.”

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event