Believe it or not, if you are someone who loves movies — the writing, the photography, the music, the design, the performance, the storytelling — you can get involved in them on a craft level.

You can make your own movie. You can go out and work on other people’s movies. It’s 2019, the technology has changed, the craft is accessible. You can, I repeat, make your own film.

Of course, it’s a tough, complicated, technical field that requires a lot of passion.

Still, I’ve made three feature films over the last decade and, for me, the journey to making my own movies has been everything from heartbreaking to beautiful. Here’s how the journey from being a person who loves movies to a person who makes movies worked for me.

Accidentally discovering movies

Whether I liked it or not, I was raised to be an outdoor kid, a boy’s boy. At any given time, my parents would have me registered to play in up to three sports leagues, usually baseball and never football (though basketball was my favorite by far).

I can’t recall either of my parents ever taking me to the movies and we didn’t have cable television, but I easily remember seeing Paul Verhoven’s Total Recall at a friend’s house when I was seven or eight. I couldn’t believe what I had experienced, and I wanted that feeling, that buzz, again.

Around this same time, Regal Cinemas built the Coventry 13 theater a mile from my house, which meant I could safely bike to the movies if and when I had the money (movies were $3.75 way back then). I went every chance I got. My best friend Teddy’s parents saw how much I loved the movies and started taking me along whenever they went. And I was in love.

A few years later my family fell apart. The consolation prize for us kids was that we finally got cable TV. TBS, TNT, USA, Showtime, HBO, even FOX on weekend afternoons — suddenly there were movies all the time. I vowed to watch at least one movie a day in 1993 and that pledge continues to this day.

I would read books about cinema. I discovered both IMDB and the Criterion Collection. Then DVDs came out and I discovered bonus features and commentary tracks.

On my 16th birthday, I started working as an usher at the Coventry 13. It felt like the most important moment of my life. I could go to any movie for free. I got free popcorn. I got free soda. My female co-workers were cute. I got jobs for my friends.

It was paradise. I wanted movies to be my life.

Eventually I started working at Musicland stores, which at that time were about 60 percent music and 40 percent movies. Perfect. Then I went to IU Bloomington and lived in the Teter dorm, which had a DVD lending library (as well as early previews of big indie films at the student union).

Trying to write

I never thought I’d be able to make my own movies, but I dreamed of doing so. I knew I could write a little, so I started working to teach myself the art of screenwriting. My plan was to read at least once screenplay a day for a year, which I did, all while writing awful first acts.

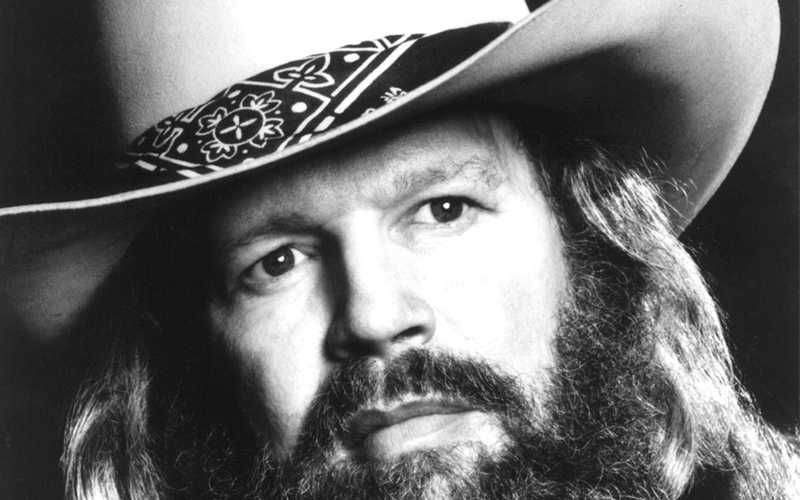

Eventually I finished a terrible, 300-page script about a guy moving back to his hometown and befriending a group of young people. Then, after that, with a new confidence, I not only started writing this column, but I also wrote a less-terrible screenplay about a group of friends reuniting on Christmas eve to unpack old baggage. All that work led me to make an artsy music documentary about singer/songwriter Lee Miles.

That film played at a handful of film festivals. Someone in New York City saw it and convinced me to move to New York.

“I can get you crew work,” he said. “You belong here.”

Filming in New York City

I believed him, and so my then-girlfriend and I sold most of our belongings and headed to Brooklyn. I worked various crew jobs (usually in the camera department) on a wide variety of productions. I can recall running camera on a terrible TV show called Dish Nation, then PAing on an even worse show called Blue Bloods, then working in the camera department on the pilot for Broad City. Later I worked on a David Wain movie.

I wasn’t a fan of industry work, so I worked really hard and made what would become my second feature film, Forever Into Space, over a two-year period. I sold paintings and records to pay for the film and called in any favor I could get. That movie got written up in The New York Times, among other publications. I played at more film festivals than I could count and was nominated for more than a dozen awards. I’d call it a small success.

In fact, that film felt like it was going to start something. I had a manager and was getting calls about distribution and doing a healthy press campaign. With that new energy, I went to work on some new scripts.

I started making a film called Queen Roosevelt. The lead actor was hit in the head by the G train about halfway through shooting. He died, as did the film.

A year later I started making a film called Get Lifted. The lead actor for that one had a secret drug problem and ended up having to leave the project about halfway through to go to rehab. And so Get Lifted died.

Then after a number of personal tragedies, I got really depressed.

Eventually, in an attempt to pull myself back together, I made a movie called Drinking Water. That film came out last year and played at seven or eight film festivals. It’s a weird little art film about two estranged friends who reunite in New York City when one friend believes the other is suicidal.

Back to the Fort

Finally, I left New York and came back to Fort Wayne. In the year I’ve been back in town I’ve started several scripts and not completed them. I’ve started shooting and editing another feature that went nowhere.

Making movies is hard.

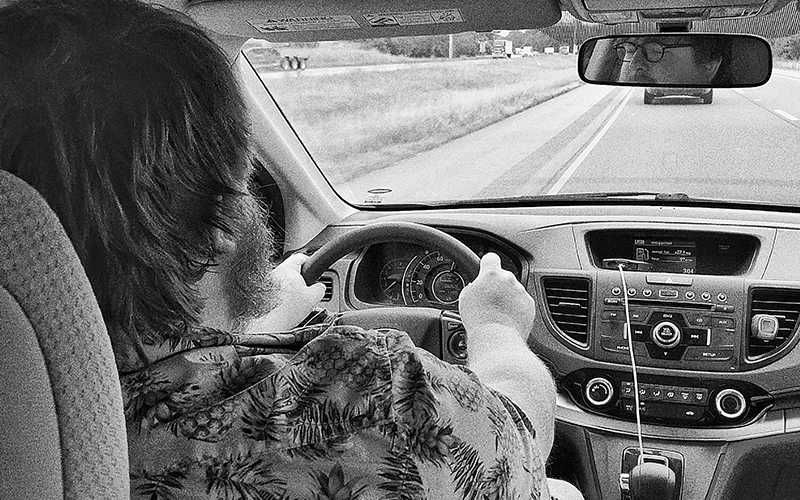

But now, as I type this, I’m happy to say that I’m almost done shooting what will hopefully be my fourth feature film. I’m out in a car, in a rainstorm in Texas, shooting a (probably way-too-artsy) road trip film with my best friend. I’m typing this with both a camera and a computer on my lap, and it feels good.

And you, film fan, could do your own version of what I’ve been doing for a decade now. I believe in you. Cinema is certainly a tough craft to get into and excel at, but I couldn’t recommend a better use of your time if you’re a cinephile.

Aside from, of course, going to the movies.