I’m sitting on the floor in Joey O’s basement on a Sunday afternoon, my back against a half-sized refrigerator full of bottled water, and watching as the Joey O Band runs through a practice session. The band is rehearsing for a gig Friday night at the Dekalb County Fair where they will open for Mr. “Rock n’ Roll Hoochie Coo” himself, Rick Derringer, who Joey says is “Playing better than ever.”

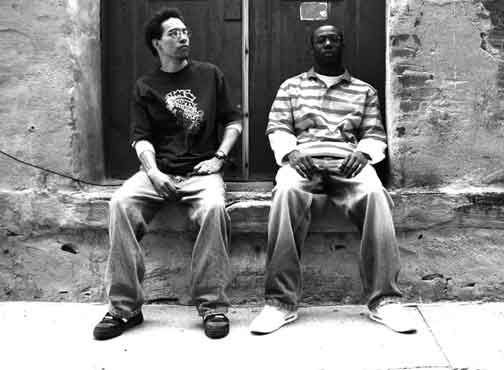

There’s Joey O, perched on a vinyl topped swivel stool, a Fender baseball cap packed down on his generous head of hair, his trademark round shades right where they should be. Standing next to Joey is vocalist Jeremy Miller. Both Joey O and Miller turn to face the rhythm section packed next to the back wall. Jon Gauthier is fingering his bass, while Justin Gillespie bounces his sticks on his drums.

Easy banter flies back and forth between Justin and Joey, who have played together for years. Joey has known Jeremy since Joey moved to Auburn over a decade ago and started showing up at the local music store to talk shop. And Jon, well, he’s from Montana, brought to Fort Wayne by Sweetwater Sound for his engineering skills. And because he’s a musician.

Joey O’s basement is not like most basements. Apart from the lack of dankness permeating the majority of basements built in central Auburn and elsewhere in the early part of the last century, this one also lacks the usual dust and spiders. What it has that other basements don’t is soundproofed, triple-thick walls and popcorn ceiling, all painted white, with carpeted floors and an escadrille of Fender amps and guitar cases. A black case, a blonde case, another black case and another blonde case, all awaiting orders. There’s also a Fender lunch box sitting on the fireplace mantel, a Fender clock and a neon Fender guitar hanging on the wall. Joey O likes Fender.

With a quick count-off the Joey O Band plunges into Stevie Ray’s “Pride and Joy,” followed quickly by “Black Magic Woman,” “Midnight Rider” and an original pop tune called “Still Dreaming.” They finish with a Led Zeppelin medley. But wait. An original pop tune? Pop? From Joey O? “This is not your father’s Joey O Band,” quips somebody. You can say that again.

“I don’t know how to describe it other than to say Britney Spears rules the world we live in,” says a frustrated Joey O as he describes his decision two years ago to hang it up after years of trying to make it as a blues guitarist. His resume is deep. Joey O has played everything from high school dances to clubs full of patrons with, at best, a limited appreciation for the blues. He’s made the rounds in Los Angeles, reached the point of being “on the verge,” been offered audition with bands like Canned Heat, The Black Crowes and Arc Angels. He’s even played with bluesman Doyle Bramhall in Texas and opened for a slew of national acts.

Despite what most would consider to be great achievements, Joey O had decided to abandon the Joey O Band and all possible future incarnations of the Joey O Band to concentrate on teaching. “I always book in advance. Through ’04 and ’05 I was simply fulfilling obligations. Above and beyond that I did nothing. I’d had enough.”

Joey Ortega grew up in Michigan and started playing drums as a kid before moving on to keyboards. In 1988 he decided to teach himself how to play guitar. A few years later he found himself in Los Angeles, meeting all the right people and making all the right moves. Music Connection Magazine’s Kenny Kerner said this about Joey O, “A star. Genuinely special … incredible strong knack for writing … an A&R’s dream … his pure pop vocals are a natural for radio.” Joey O received a rating of 8 (out of 10), the highest rating ever in publications demo critique section.

There is just one problem, “By the time I was getting established in L.A., Poison and New Kids on the Block were big. Where do I fit in? When record companies started talking to me, Nirvana was the biggest thing in the world. Here I was a good-looking, well groomed guy and bad hygiene was all the rage. I was a fish out of water.”

Also, it seems, blues is not at the top of the demand list. “L.A has a larger population than Canada. Besides me there was (maybe) one other blues guitarist in town. That was scary.”

So Joey O waves goodbye to La La Land and heads east, eventually settling in Indiana to regroup. He considers Buddy Guy. “Here’s Buddy Guy venting on some radio station or something somewhere. Buddy Guy has sold something like 2 million records his whole life. Wilson Phillips’ debut record sold 10 million. Vanilla Ice has outsold him. What does that say about the industry?”

Then comes a call from the Black Crowes management. They’re looking for a guitar player and ask Joey O to audition and, if he makes it, to become a party in the various lawsuits the band has going. It would have been an odd pairing, anyway, considering Joey O doesn’t drink or do drugs. Canned Heat calls, too. They want to fire their guitar player and ask Joey to audition. Back and forth phone calls ensue. Then their bass player quits and they decide to keep the guitar player and just replace the bass player. “At the end of the day, teaching guitar doesn’t sound so bad,” Joey says.

Last September he finds himself with one more gig to play. One more obligation to meet, nearly all of the crap involved with playing cover tunes in smoky bars gone forever. One more commitment and then he’ll be through. No more bar owners to haggle with, no more chasing gigs to stay busy. But, he also finds himself short a bass player and a vocalist. So he calls Miller, who calls Gauthier and they go to the gig and basically wing it and have a blast.

A year later, and Joey O is in his basement with Miller, Gillispie and Gauthier running through Led Zeppelin songs and working on their own songs for a CD. And if “Still Dreaming” is any indication, the record will be very good. Things are great; Joey likes his band, and his band likes him. He’s got a DVD of his career in the works complete with students he likes. He has another month-long trip to Germany coming next year and sporadic gigs.

“I didn’t plan this band. It just fell into my lap, and I feel lucky for it. I work in a music store giving guitar lessons. Every week some guy in a band is complaining about somebody else they were in a band with. I feel fortunate that we really like each other. That made a world of difference. [There’s] got to be some reason to continue doing it.”