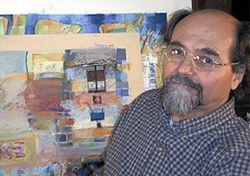

To distill the essence of local painter Michael Poorman’s recent work

is to retrace the artist’s own 40-plus-year journey of collecting,

discarding, incorporating, dismissing yet always embracing the world

of the creative process.

Not easily discernible, Poorman’s message of universalism, unity

and a kind of mystic clarity reveals itself only after the viewer

seeps himself in the rich hues and subtle shades of his expressionist

ink and oil pastel pieces. Helpful clues are revealed in the familiarity

that comes from knowing the 60-year-old, who spent several years honing

his photographic skills before returning to his first loves of drawing

and painting.

His works have been and are featured at the 1911 Gallery, Castle

Gallery and Artlink among other venues although frankly they deserve

an even wider audience and acceptance, i.e. read “Note to FWMA acquisition

committee.”

Poorman’s been “practicing” his craft for more than 40 years,

supporting himself along the way for the most part as an architectural

draftsman. Even in this “day job” he has built a solid reputation

as one of the few experts in producing hand renderings of proposed

projects, usually on a strict deadline.

As one prominent local architect and long-time user of his services

relates:

“He’s simply awesome. His work is super. Whether he whips out

a hand rendering with magic markers, colored pencils or ink, his

output is of the highest quality.

“He is such a nice fellow too, easily one of the most popular

people in the business. That, and because he is so meticulous,

he’s an easy target for our practical jokes. It’s not uncommon

to sneak into his office when he’s away and sign a drawing,

maybe a couple of times, then wait to see if he catches it.

Of course it works the other way too. Like feigning criticism

and telling him the piece isn’t good enough to usurp credit for.

In either case he has a great sense of humor and everyone recognizes his immense talent.”

In his current showing at the 1911 Gallery, Poorman offers us a

selection of oil pastel and ink pieces. These delightful, upbeat renderings, blend a pallet of orchids, oranges, yellows, golds, and reds.

They are, for the most part, friendly pieces, reminiscent of Hans Hoffmann’s colorist ventures from the late 1950s.

Like certain of his musical idols from the same period – Miles Davis, Bill Evans and John Cage – Poorman’s recent works are a model

of restraint, where the “less is more” theory has established dominion.

With his Homage to John Cage, Poorman fuses his deep and abiding interest in music with multihued variations.

As in Cage’s famous work Silence (the book and the score), he succeeds in playing a muted timbre.

On a defined and distinctly vertical staff, he scores his lyrics atop one another. The colors cascade like a lighted water fountain.

In contrast, the surfaces of his Comix series are less contained. There, the subtle primary tones are freed to mix with one another.

Knocked down in their intensity, the resultant colors churn and go awash like those spilling from beached waves.

David Krouse, gallerist at the 1911 Gallery, will also talk to you about Poorman’s

sophisticated composition and his use of color and musical themes.

“I find in his work an honesty and exceptional quality that is so strong, not just among local artists but anyone working

anywhere these days. He’s a hero of mine and I’m not embarrassed to say that.”

‘

Poorman’s minimalist works can’t be deconstructed to a means of message bearer. Whatever his scripts set out to convey,

they ring with elegance, echoing Paul Valery’s quip: “I stop saying in order to make.”

“I’m not certain why I chose oil pastels,” explained Poorman. “It was really a kind of experimental thing.

But using these sticks – a kind of cross between chalk and crayon — forces me to work considerably slower than if

I were applying paint with a brush. As it turns out that’s been a good thing.”

After enjoying a brief but intense period of recognition in

high school at North Side, Poorman studied under Noel Dusenchon,

Don Kruse, Russ Oettle and George McCullough at the old Fort Wayne Art School.

From there Poorman moved on to the John Herron Art School in Indianapolis

before ending up in San Francisco in the early 1960s with a family.

To support them he managed a string of movie houses, which gave him

ample time to see (sometimes over and over again) lots of first-run

and not-so-first-run films.

“I appreciate the training and life education I got from that group at the

Art School and at Herron,” explained Poorman, “but I have to say that it was a

trip to a San Francisco Museum and a confrontation with Robert Rauschenberg’s Canyon that really affected me.

“Since high school I had been a subscriber to the ‘Evergreen Review,’ and I was familiar with the work of the New York

School. Painters like Jackson Pollock, Willem deKooning, Franz Kline excited something in me, but when I discovered

Canyon and some of Rauschenberg’s other pieces along with Mark Rothko, Jasper Johns, Jack Tworkov, it was an awakening.”

Rauschenberg’s combine Canyon was created in 1959. It combines fabric, cardboard, paper, photographs,

metal, paint and other elements with collage work and several

striking 3D elements – namely, a stuffed bald eagle perched on a box and a suspended pillow.

The piece exemplifies Rauschenberg’s theory about everyday objects as art

and has become a high water mark in the modern art continuum.

The NY School and abstract expressionism had for the most part held sway over not

only modern art but in academic circles as well. However during the late 50s

other artists and musicians were independently throwing away the burden

of angst and seriousness and the existentialism that emerged seems very much with us today.

Back in San Francisco and without a proper studio to work in,

Poorman fell back on his other passion, photography.

“It was partly taking photos in a great arena, like San Francisco, and it was also a means to meet others,” said Poorman.

“But eventually I was nailed by a friend who told me that my camera – that contraption –

was hardly a substitute for my painting and drawing. That challenge haunted me for years until I found a reason to pick up my pencils again.”

Frame and field held sway over Poorman’s eye for several years, including his return to Fort Wayne.

He worked as a professional photographer, covering weddings and other events, using his

earnings to bolster his tools, i.e. one wedding equals a flash.

Another earns special lighting. Some portraits got him a better light meter, etc.

As it turned out it was the most sublime of reasons that prompted Poorman

to re-embrace his art.

“A friend was about to have a birthday, and she wanted a map as a gift. That was too easy,

so I got the map, then opened my pencil box and began to create a piece over it.

She got her present, but I think it was three months after her birthday.”

Forever the collector (some would say archivist of film and music), Poorman remains a witness

to the shifting sensibility in all the arts during his life. A student and collector of popular

music, he heard Perry Como, Elvis and the Platters like his fellow high school chums,

but he also listened to Bo Diddely and the mainly ‘race’

rhythm and blues tunes on WLAC-AM out of Nashville. There he heard, only on clear

nights, not Pat Boone but Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Lightning Hopkins, Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf and Etta James.

Cruising for burgers and chasing poodle skirts between football and track practice was the norm

(Poorman was an integral part of North Side’s state track titles under the legendary Rollo Chambers).

J.C. Whitney catalogs were hot topics, nonetheless he also found time to discover Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and John Coltrane before it was cool.

In an era dominated by Norman Vincent Peale, Vance Packard and Ayn Rand, Poorman sought relative

relief in reading Kerouac, Ginsburg, Snyder and Ferlinghetti. To counter-balance Bishop Sheen

he studied Alan Watts and Cage.

While the Hollywood Technicolor fare of Pillow Talk and Rio Bravo

drew friends to the movies, Poorman found solace in the grainy black and

white French New Wave cinema of Goddards Breathless, Truffant’s 400 Blows and Fellini’s

La Dolce Vita.

Ultimately Poorman found a balance and has built upon it.

In his “day job” Poorman creates practical objects. At his “night gig” he

produces useless things as a compensation for not having worked and made

something useful. We accept these gifts because they are ultimately

beautiful, interesting, furtive and most genuinely worthy of our attention.

Poorman’s current work is a part of the 1911 Gallery exhibition lasting through January. He’s

there along with Suzanne Galazka, Michael Rader, Tim Brombleoe, David Birkley and Richard Fizer plus David Krouse.

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event