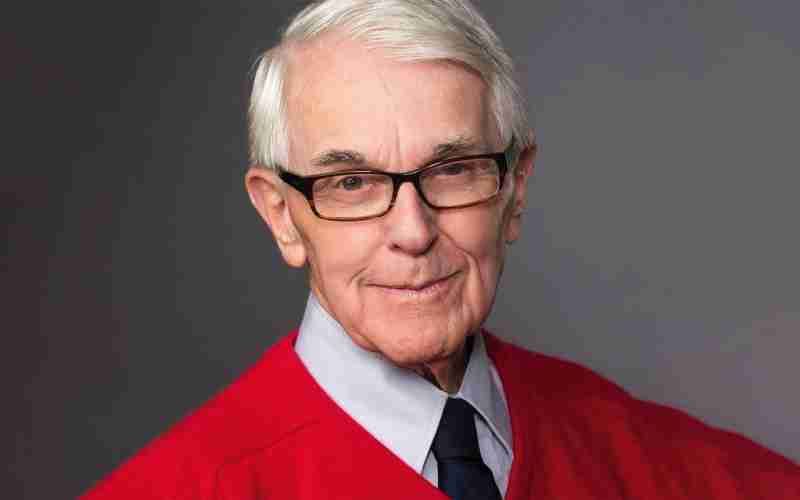

I defy you to name a nicer person than Harvey Cocks.

It simply can’t be done. A particularly impressive feat considering he happened to be a Broadway star in the 1940s and 1950s and is one of Fort Wayne’s most prodigious name-droppers.

Born 88 years ago (his birthday is in two weeks) in Glen Cove, Long Island, Cocks grew up in vaudeville. His father, a theatre manager, took his young son to rehearsals. “They called me ‘the Boy on the Box,’” he says. “They put a box in the wings for me, and I would sit and watch the performers.”

His earliest memory was a 5 a.m. vaudeville rehearsal in Boston. “I was four years old,” says Cocks. “A man came out onstage and sang. I asked my father, ‘Who was that man with the funny voice?’ It was Al Jolson. He said, ‘Remember that name. He’s going to be somebody.’ He was very nice to me.”

With his upbringing, a career in theatre seemed a natural progression. But he now attributes the lure of the theatre to his innate shyness. “I moved around a lot,” he says. “I didn’t have any friends. I was the outsider. I didn’t want to be a movie star. It was always the theatre. The theatre actors were untouchable.”

His family moved to Fort Wayne where his father managed the Embassy Theatre, and soon after high school graduation he moved to New York. Astonishingly, the 18-year-old booked a Broadway role on his first audition and was soon offered a role in the long-running hit Life with Father.

Cocks became a triple threat, thanks to cast mate Nancy Walker (who went on to star as Valerie Harper’s mother on Rhoda in the 1970s). She asked him if he wanted to make the stage his career, and he said he did.

“She said, ‘Well, you’ve got to sing and dance,’” he recalls. “I said, ‘I do?’ She said, ‘What are you doing tomorrow?’ So the very next day she took me to her voice and dance teachers.”

For the next five years he worked steadily and exclusively in musicals. “Pal Joey and Finian’s Rainbow were my bread and butter,” he says. “I jobbed myself out to every summer stock theatre on the East Coast in those two shows.”

Although Walker’s advice helped pave the way for a long acting career, he says the person most influential to him was playwright and director Howard Lindsay, who wrote Life with Father.

Lindsay and his Anything Goes co-writer Russel Crouse heard that Cocks was interested in playwriting. “So Saturday mornings before the matinee, they would take me to their office,” he says. “I wrote scenes and they would critique them.

Even the stage manager took him under his wing. He heard that Cocks was interested in directing as well, so he pulled the entire cast together to rehearse a show at 11 a.m. before every Saturday matinee for eight weeks.

When it came time for the performance, Cocks laughs, “I was terrified! Katharine Cornell [one of the great stage actors of 20th century American theatre] walked in, saying, ‘Is this where the play is being performed?’ The Lunts were there, Helen Hayes … They were Howard [Lindsay] & [cast mate] Dorothy Stickney’s friends.”

Quite the directorial debut for a young man in his 20s.

He paid this generosity forward as well. He spent his Sundays teaching theatre to orphans in the Bronx (“My career at the Youtheatre was almost forecast,” he muses). As a director, he says, “I gave a lot of work to a lot of set designers and props people. I was always trying to give work to people.”

He also discovered Oscar and Tony Award-winning actress Sandy Dennis, an apprentice at the summer stock theatre he ran. “She studied with Lee Strasberg,” he says. “She was very natural. She was in Diary of Anne Frank, and she wanted to do all the normal things [onstage], like scratch and stick her tongue out. Very realistic. But we weren’t into that [acting style] yet. We had arguments all the time, but I was very impressed with her.”

Another actress who impressed him was Jean Hanson.

Immediately upon return from two and a half years of Army service in Europe, Cocks booked a Broadway lead. To steel his nerves, he decided to visit his voice coach and singing teacher (a mother and daughter team) at their New York apartment.

“I waited in the hallway, and I heard a voice singing in the room,” he says. “I waited my turn and just listened to this voice. And then she started talking. This throaty, wonderful voice. And I think I started to fall in love right then.

“Of course, I’d been engaged several times before this,” he says with a chuckle. “I fell in love with every ingénue I appeared with.”

The teacher introduced them, and he asked her to dinner on the spot. “She must have thought, ‘Who is this nut?’” he laughs. “I knew then that was the girl I was going to marry.”

This was in 1952. They married six years later and remained married until her passing in 1994.

In 1971 they moved to Fort Wayne to help his father run Quimby Village during his ill health. He intended to stay for just a few months, but his wife had already fallen in love with the city.

“Jean had been a successful dancer,” he says. “She had a contract to be in the original Gypsy but broke it to stay in Fort Wayne.

“My wife and I never would have stayed if there were no philharmonic, no ballet, no theatre,” he says. “This is such a unique town.”

After his father died, Cocks sold Quimby Village and took a public relations job for a local hospital. But migraines that plagued him during times of stress forced him to quit. When Youtheatre President Roberta Daniels called and offered him the role of executive director, he jumped. He has remained with the Youtheatre for the past 35 years, although he stepped down as executive director a few years ago.

Over the years, some 16,000 students have been through Youtheatre classes or productions. One of those alumni is now the Youtheatre’s new executive director, Leslie Hormann. “You can’t find a single community show that doesn’t have a Youtheatre student in the cast,” she says.

Cocks estimates that at least 50 of his former protégés are now working professionally in theatre on both coasts. And he says a week doesn’t go by that he doesn’t run into one of his former students.

Given Cocks’ years of helping foster the talents and careers of actors, directors and technicians of all ages, it seems only fitting that he should be the first recipient of whatzup’s H. Stanley Liddell Award, presented at last week’s Whammy Awards.

Liddell, a business owner much like Cocks’ own father, owned the Marketplace of Canterbury and Piere’s, which became the area’s premier nightlife hub, bringing life to the Fort Wayne music scene. Not only did he bring national acts to Fort Wayne, he showcased local talent. Like Cocks, he recognized the talent Fort Wayne had and believed in fostering that talent to help improve the community.

“It really is wonderful they named this award after Stan,” Cocks says. “He truly put Fort Wayne music on the map.”

In presenting the award, Hormann recalled her first meeting with Cocks in 1976 when he first took the Youtheatre position. “I was a Youtheatre student,” she says. “I was this ugly adolescent, this crazy, loud, obnoxious 13 year-old with a mouthful of braces. The teenagers were all abuzz that the new director was a Broadway star. And he made a point of telling me how wonderful I was. It meant so much to me.”

It’s connections like these, more so than the glamorous career and famous friends, that mean the most to Cocks. He says his Youtheatre years have been the best years of his life.

“It’s been a labor of love,” he says. “It’s kept me young.”

Submit Your Event

Submit Your Event